THOMAS SULMAN (1832 – 1900)

Thomas Sulman was an English architectural draftsman. He studied at The Working Men’s College between 1854 and 1858, where he was a student of, and later an engraver for, Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Sulman drew and engraved images for newspaper and magazine advertisements. While his work may have seemed glamorous and exciting, Sulman appears to have been a modest man, and relatively little is known about him. We’ve done some digging, to try to reveal the man behind the maps.

EARLY LIFE

Sulman was born on 21st July 1832 in Islington, London and raised by his parents Thomas, a watchmaker, and Mary. At the age of 18 he is described as a ‘draughtsman on wood’ in the 1851 census. The family was clearly comfortable, and has one servant.

His family were church goers and seem to have instilled in him a charitable outlook. His parents were involved in the establishment of a ‘Ragged School’ – charitable organisations dedicated to the free education of destitute children – in Waterloo, where Sulman eventually met his wife, Mary.

DRAUGHTSMAN

Sulman trained as an engraver and illustrator at the Working Men’s College in London. Founded in 1854, and still in existence today, their ethos is the provision of adult education for those who have otherwise struggled to receive it.

22 year old Sulman entered the College on its opening. Memories of his time there are captured in an article in Good Words journal (1897, pp. 547-551), where he describes art classes taught under the instruction of one John Ruskin;

“Never without an afterglow of grateful memory will the first art class of the Working Men’s College be remembered by those few living who were privileged to belong to it’.

The college boasted Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Ruskin, William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and Ford Madox Brown among its early teachers. Instruction in art at the college was thus decidedly Pre-Raphaelite.

By 1871 Sulman is living with Mary and their three children at Chetwynd Villas, London. The house would have been brand new, in an area described by Charles Booth, the philanthropist who surveyed poverty in the capital, as ‘Fairly comfortable. Good ordinary earnings.’ They had Sulman’s mother living with them, as well as a servant, and an apprentice, Charles R Wilson. This is right in the midst of his time working for the Illustrated London News, so we can assume he’s doing fairly well.

THE MAPS

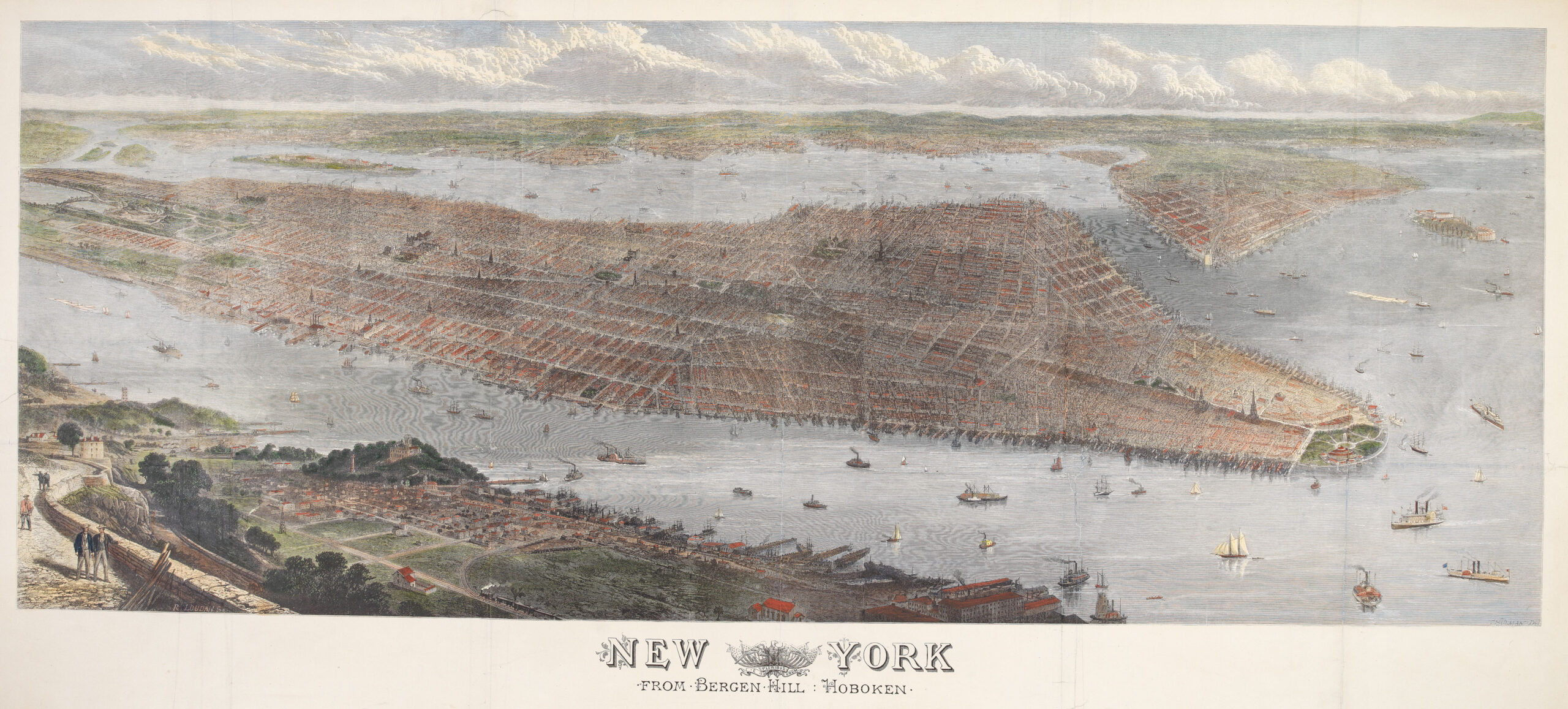

A number of online sources tell us that Sulman became a specialist in using balloons to produce birds-eye views of cities including London, Oxford, Glasgow and New York City. However, we have no evidence of the process that Sulman used. He was an architectural illustrator, and our best guess is that he used a combination of hot air balloon, photography, and Ordnance Survey mapping to create his illustrations. These views, as hand coloured engravings produced with the help of London engraver Robert Loudan Sr., were featured in The Illustrated London News from the 1860s, and were sometimes produced to a fold-out six foot length.

Our Bird’s Eye View of Glasgow, 1864, was engraved by Sulman and included in the 24th March 1864 issue of the Illustrated London News.

Other panoramic maps produced by Sulman include:

1861 – London

1865 – Liverpool

1868 – Edinburgh

1872 – Boston

1876 – New York

1887 – Newcastle

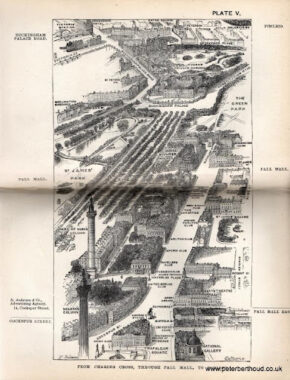

In 1891 he produced high-level views of major London thoroughfares for Herbert Fry’s London: Illustrated by Twenty Bird’s Eye Views of the Principal Streets engraved by George William Ruffle (1838–1901).

POSITIVISM

Sulman was influenced by Positivist thinkers at the Working Men’s College and became part of the Church of Humanity, inspired by Auguste Comte’s religion of humanity in France.

Positivism captured the Victorian imagination. It held the interest of thinkers as diverse as Annie Besant, HM Hyndman, John Ruskin, Charles Booth and Beatrice Webb. The branch of the Church of Humanity that Sulman was part of was very much a ritualistic religion. It is often seen as an eccentric passing phase – a curious ‘Catholicism minus Christianity’ – is a popular quip.

Comte stated that the pillars of the religion are:

- altruism, leading to generosity and selfless dedication to others.

- order: Comte thought that after the French Revolution, society needed restoration of order.

- progress: the consequences of industrial and technical breakthroughs for human societies.

Comte “made art an integral part of his system and attributed to it a leading role” in his new Positivist society. For Comte certain social conditions were necessary for art to flourish – namely that the relationship between artist, spectator and society had to be harmonious and stable. This interpretation of the function of art was very closely related to that of Ruskin, William Morris and the followers of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

It was a response to rapid urbanisation, imperialistic wrongs and the Victorian crisis of faith.

GALLUS-NESS

On his sudden death in November 1900 following a seizure, a memorial sermon was preached at the Church of Humanity 16 December, 1900 by his friend Henry Crompton (CROMPTON, H. (1901). Thomas Sulman: a memorial sermon. London, Church of Humanity).

It’s clear from Crompton’s words that if Victorian Glasgow was gallus – bold, cheeky and flashy – Sulman was the opposite.

“He lived for others. He was loved by all who knew him…If he had faults we knew them not: unless the fullness of his generosity could be deemed a fault. In him it seemed a glorious virtue. In him it was a generosity which issued in true charity – charitable judgement of other lives, generous appreciation of others’ labours.”

“He was my intimate friend for more than thirty years, and yet I cannot remember a single angry word from him, spoken or written, or any gesture of impatience or anger.”

Considering the world that Sulman lived in – enjoying global travel, professional success and association with great artists and thinkers of the day – little is known about the man himself. This is borne out in Sulman’s eulogy which states that, “outside his family, there were no great events to record of him.”

“If his life has been simple, it has been beautiful : life as it should be, without great disturbing or exciting events, of constant culture, improvement, and development.”

LEGACY

Sulman’s youngest child, Dora, follows in his footsteps and becomes an illustrator. Dora Sulman was at the famous Slade Art School with another famous illustrator Ethel Walker, during the time often referred to now, as the “golden age of illustration” before World War 1.

Following her father’s death, Dora took over his offices near Lincoln’s Inn Fields and the Royal Courts of Justice in London, where he had shared premises with solicitors, architects & surveyors. Later, Dora had a Thames-side studio at Chelsea, and she was great friends with other artists of that period such as Clare Atwood, Beatrice Bland and Eleanor Best. She created illustrations for books and advertisements.

In the directions Thomas Sulman left for his family upon his death, he wrote the words,

“Think of me always as saying to you all, Love is enough.”